Since every level of the value chain now seems to require a complex web of suppliers who consume products and services of others with which they then provide products and services to their customers, supply chain risk management is yet another demand on the enterprise’s attention. Although cybersecurity risk within the supply chain was added to the NIST CSF in 2018, the recent events surrounding SolarWinds have taken us from debate and thought exercise to reconsidering the very tangible consequences of compromises in our core information and technology systems.

This is the first in a series of blog posts that will be undertaken by the Caffeinated Risk authors which will include both reflection on third party risk management programs implemented for enterprises and review of the most current guidance from organizations such as NIST, ISACA and ISA. Additionally we will be exploring potential mitigation approaches when the limits of standards and best practices leave residual risk unacceptably high.

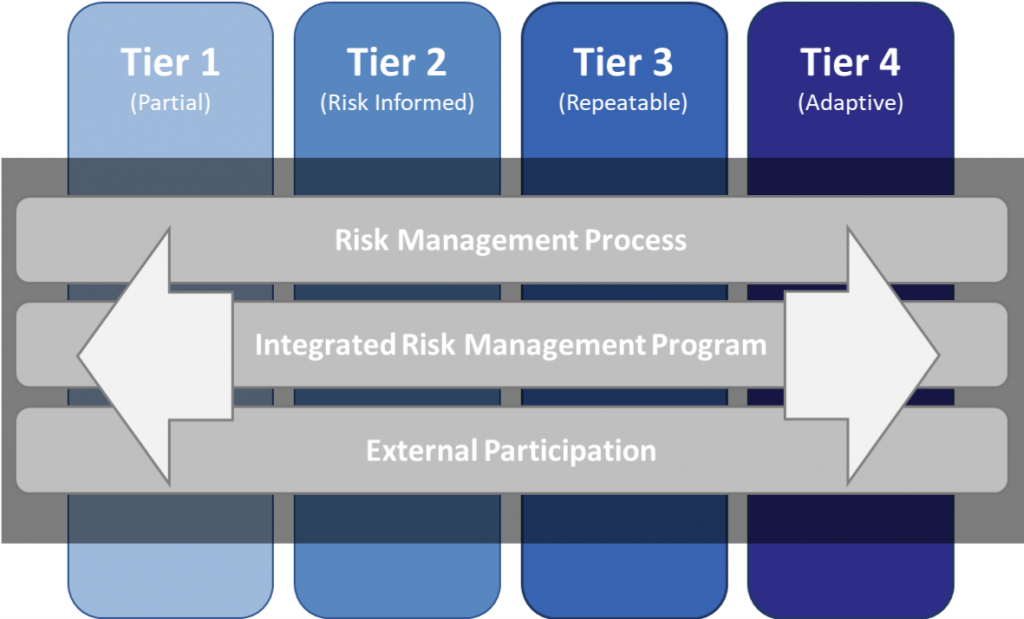

Supply Chain Risk Management is now a specific NIST CSF category, (ID.SC), with five subcategories ranging from the more basic awareness and stakeholder agreement to recovery planning testing with suppliers. In addition to the core framework the CSF includes two additional components, tiers and profiles, which could support an organization defining the the appropriate level of risk management required for a specific capability. It is all too common for a blanket policy statement like “all systems will meet maturity level X.X” without consideration of their impact to the organization in the event the capability is compromised. While each organization is different, the blanket approach results in uneven levels of residual risk across the enterprises information and technology systems, often without a way to identify actual exposure since compliance to the defined level is what’s measured.

Effectively communicating risk to stakeholders is never simple so measurement against standards is often the agreed path. A lighthearted quote from a manager many years ago, “the best part about standards is there are so many to choose from”, didn’t make much sense when I was new in my career but decades later the irony has fully set in. On more than one occasion I have observed knowledgeable people debate control or security levels, later determining they were referring to different frameworks. NIST insiders may have also observed confusion at some point, as this guidance in implementing CSF tiers includes a differentiation with NIST security maturity levels.

“Tiers do not necessarily represent maturity levels. Organizations should determine the desired Tier, ensuring that the selected level meets organizational goals. Reduces cybersecurity risk to levels acceptable to the organization, and is feasible to implement, fiscally and otherwise.” NIST online learning

The tiers in the diagram above are described in detail by NIST CSF section 2.2 and can be used in both the assessment of current state and definition of a target state. The interesting nuance is the up front identification that each organization’s objectives will be unique and not all systems within the organization may need to have risk managed to the same level.

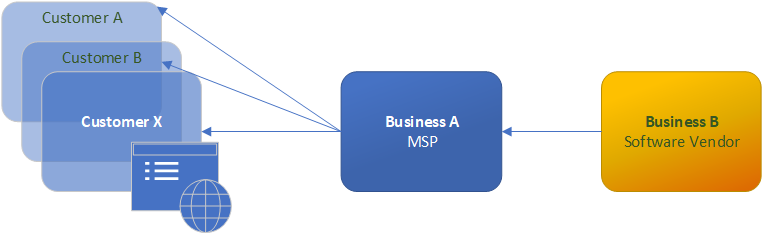

There is no need to rehash NIST CSF section by section, the resources are freely available to all. Instead, we are considering the supply chain security issue and how those risk profiles may appear in organizations within a credible but completely fictional scenario involving an I.T. managed service provider using a well established commercial software suite to monitor the networks and applications of it’s numerous customers.

When an organization’s risk management practices fit into the NIST Tier 1:Partial category risk management is ad-hoc or reactive. Within the context of the cyber supply chain the majority of the people in this organization would be generally unaware of how their activities affect their clients and would not likely be monitoring their suppliers for any cyber security issues. This lack of awareness could easily compound as businesses source from other businesses with similar ad-hoc risk management programs.

If the I.T. managed service provider, (MSP), in this scenario has only a partial awareness of their impact in the supply chain they may overlook the cyber security practices of their input sources and focus more on meeting day to day operational requests from their clients. The customers of this MSP also in the NIST CSF tier 1 category are likely more focused on service level agreements, cost management and maintaining other parts of their business, essentially assuming everything is handled. Since many managed service provider contracts are outcome based a customer may not feel they need to be overly concerned with the software stack used by their MSP. A deeper dive into the COBIT 2019 and NIST 800-53 practices referenced in the ID.SC subtasks actually contradict this assumption and shine a light on where a tier 1 risk profile needs to begin improving.

“Identify and manage risk relating to vendors’ ability to continually provide secure, efficient and effective service delivery. This also includes the subcontractors or upstream vendors that are relevant in the service delivery of the direct vendor” COBIT 2019 APO10.04 Manage vendor risk

We can advance this fictional scenario by upgrading the risk management program tiers of both the I.T. MSP and Customer X to “Risk Informed”. The means the cybersecurity risk management practices are established at the management level but not effectively observed across the organization. “Risk Informed” can often take the form of written policies or even contractual clauses related to the ID.SC subtasks but interpretation and implementation is likely still missing on the front lines.

Due to the large amount of attention created by the SolarWinds compromise the I.T. workers at the fictional MSP may have taken it upon themselves to look into possible issues or they may have received a notification from the software vendor. Regardless of how the staff was advised, the response efforts were likely not well coordinated internally due to a lack of well understood roles and procedures.

Although FireEye did an excellent job of getting positive indicators out to the public quickly industry experts were quick to caution that not finding positive compromise indicators didn’t remove the need for deep investigation for anomalous behavior. These types of investigation take time and considerable skill, placing a lot of extra demand on I.T. and security staff. It would not be uncommon for the service provider not to initiate communication out to their clients due to ongoing investigation activities. The communication breakdown was not because something was being hidden but a lack of incident response processes that include stakeholder communication commitments. Similarly, Tier 2 customers may not have seen the need to reach out to their service provider to see if the software compromise is affecting or potentially affecting the service they are currently receiving. From their perspective, as long as the systems are up, everything must be okay.

To reach Tier 3: repeatable, the organization is aware of the cyber supply chain risks associated with the products and services it provides and that it uses.

Returning to our scenario Customer X has contracted the MSP to ensure their customer engagement solution is available 7X24 and responsive. This website is very important to both their brand reputation and revenue stream because service disruption and degradation drive customers to the competitor. Company X is also aware cybersecurity issues can appear, seemingly overnight, with technologies that were previously considered safe. They may have learned this lesson the hard way in 2014 when many websites were shutdown during the first few days of Heartbleed due to customer data actively in memory on those websites suddenly being accessible to anyone capable of running a python script.

Since Customer X is risk aware, their risk management process includes people within their organization who are accountable to know the customer engagement solution is being actively monitored by a third party, how that monitoring being done meets their needs and the level of cyber security capability/maturity of that external party. We can assume that the I.T. MSP was hired because they had a reasonably priced service offering and repeatable risk management practices which would be part of a tier 3 customer’s vendor selection criteria. This assurance may have been achieved through extensive vetting via questionnaire, process document reviews or even an onsite assessment.

If we are willing to accept that resilience is a much more pragmatic approach to cybersecurity risk management than insisting on prevention for all possible scenarios then NIST CSF Tier 3 is likely where we need all be aiming as a minimum goal for systems that meet the required criticality within the organization.